US and UK strikes fail to slow Houthi attacks

Repeated US and UK air strikes against the Houthis in Yemen have failed to slow their attacks on ships in the region, BBC Verify has found.

There have been nine attacks on ships in the past three weeks, compared with six in the previous three weeks.

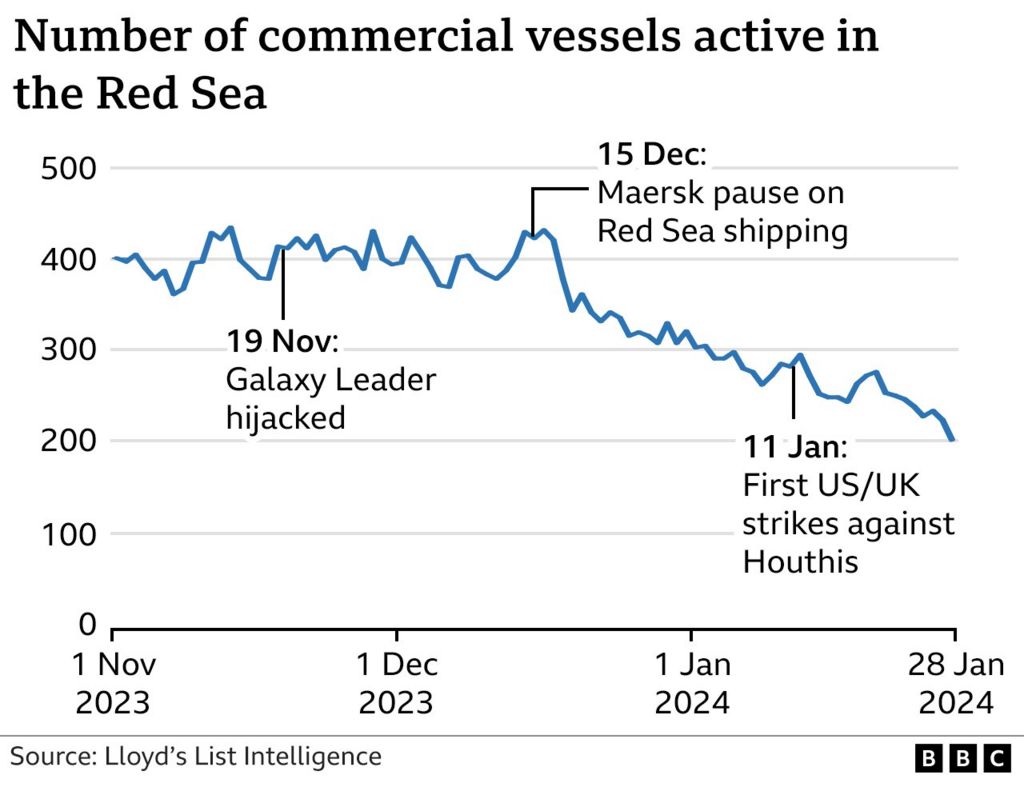

Since the US-led strikes began on 11 January, shipping using the vital Red Sea trade route has dropped by 29%.

That’s a greater rate of decline than between the start of Houthi attacks in November and the beginning of the US-led action.

Change of tactics

The Houthis initially said they were attacking ships connected to Israel, or heading to or from there. But since air strikes began in January they have mostly targeted ships tied to owners or operators in the UK or US.

In total, 28 vessels have been targeted since Houthi attacks began in November. We’ve identified seven of these with links to Israeli companies, individuals or destinations.

BBC Verify has used vessel tracking data and official company records to establish these ownership links where possible. However, identifying vessel affiliation is not a straightforward process as multiple layers of company ownership can be difficult to penetrate.

Of the nine ships attacked since the air strikes began, five had American or British links, and none had identifiable Israeli links.

As well as their targets, their tactics have changed.

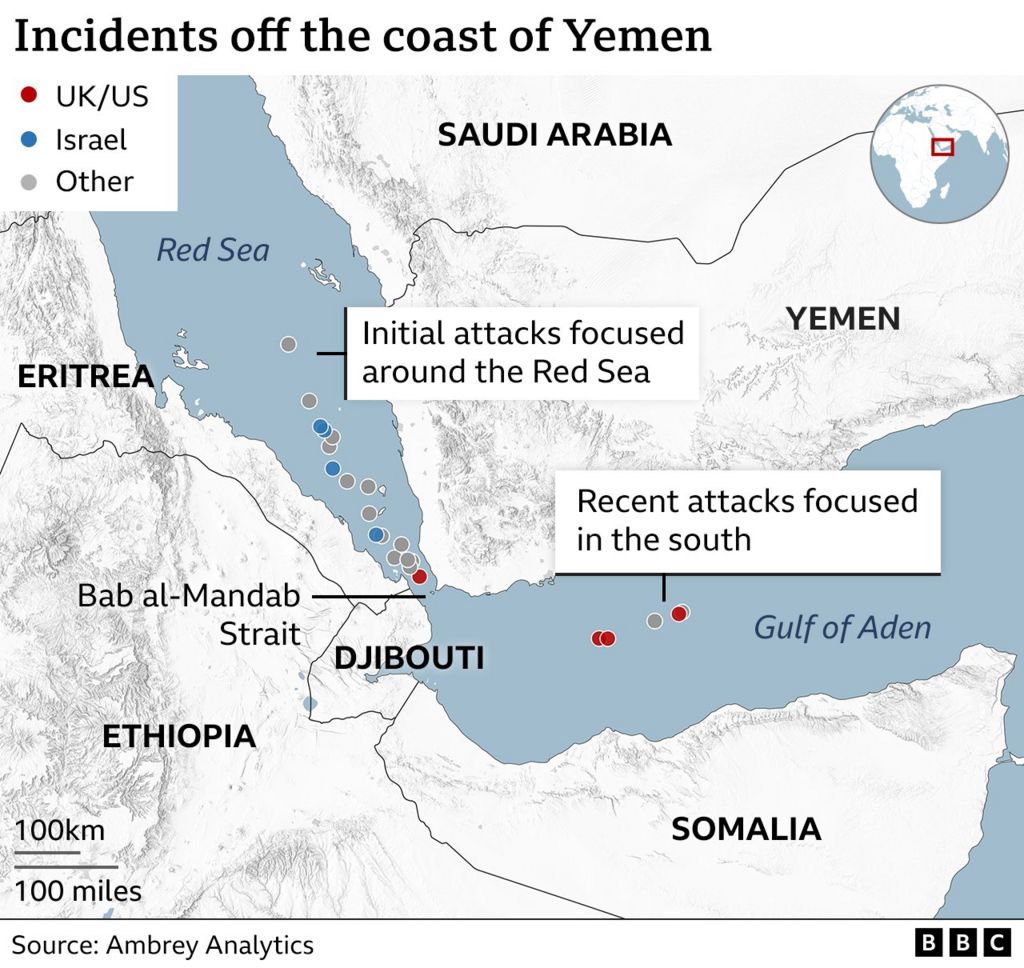

In November and December, their attacks were concentrated at the southern end of the Red Sea close to the narrow Bab al-Mandab Strait where ships are forced to sail very close to the coast of Houthi-controlled Yemeni territory.

In recent weeks they have been mainly striking further to the south in the Gulf of Aden.

The Houthis have also changed how they attack. Initially they used both missiles and drones carrying explosives, but more recent attacks have used mainly missiles launched from Yemen.

The Red Sea is a key shipping lane, and the most efficient way to transport goods between Asia and Europe.

But the number of commercial ships using the route has fallen by 50% since the start of the Houthi attacks, according to ship tracking firm Lloyd’s List Intelligence.

This is despite a US-led military partnership, involving UK naval vessels, safeguarding commercial shipping in the area.

It does not seem that the fall-off was seasonal as there was no similar pattern of decline in the same period last year.

How did the decline come about?

There was no perceptible initial response from shipping companies to the hijacking of the Galaxy Leader on 19 November.

But ship tracking data shows that this changed from 15 December, when ship operators began taking decisions to re-route their cargo around Africa. The decline in ships using the Red Sea has continued in the weeks since, despite significantly more fuel being needed for the alternative route, as well as higher crew wages and insurance costs.

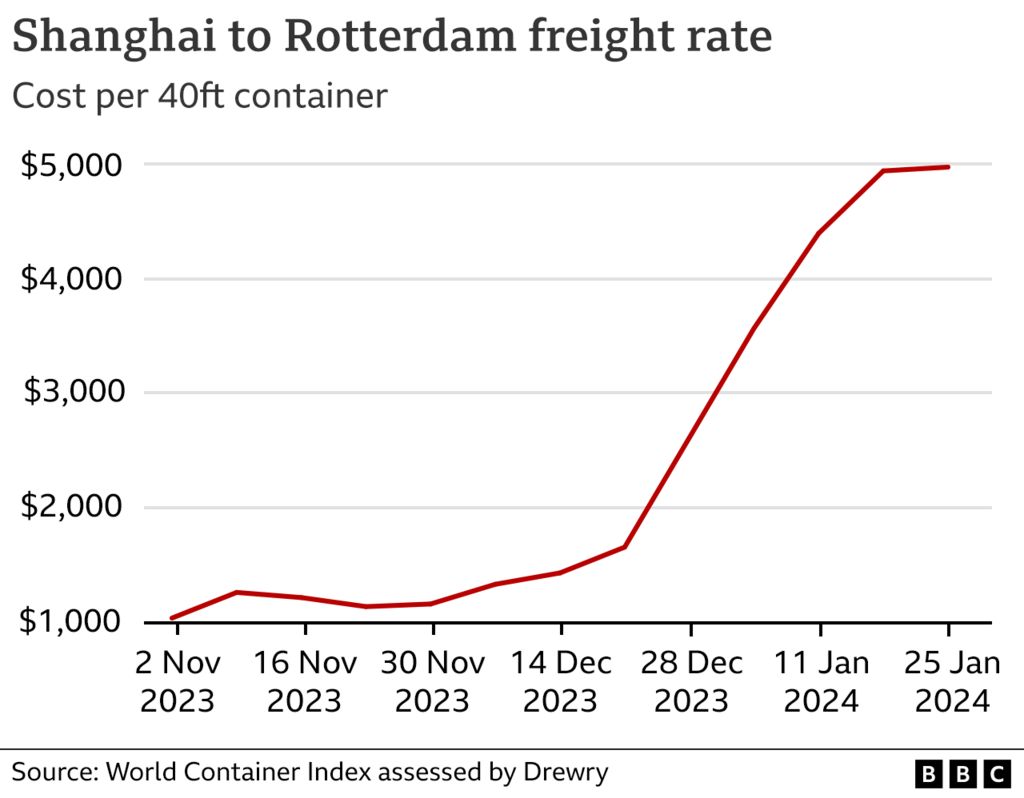

As an example, the cost of transporting a standard 40ft container from Shanghai to Rotterdam has risen from about $1,200 (£940) in mid-November to almost $5,000 at the end of January.

As freight charges rise, there will inevitably be pressure on the prices of all manner of consumer goods from fuel to food.

Sailing from the Middle East to Europe around Africa, instead of through the Suez Canal, can add three weeks to the journey time and cost over $2m more, according to price reporting firm Argus Media.

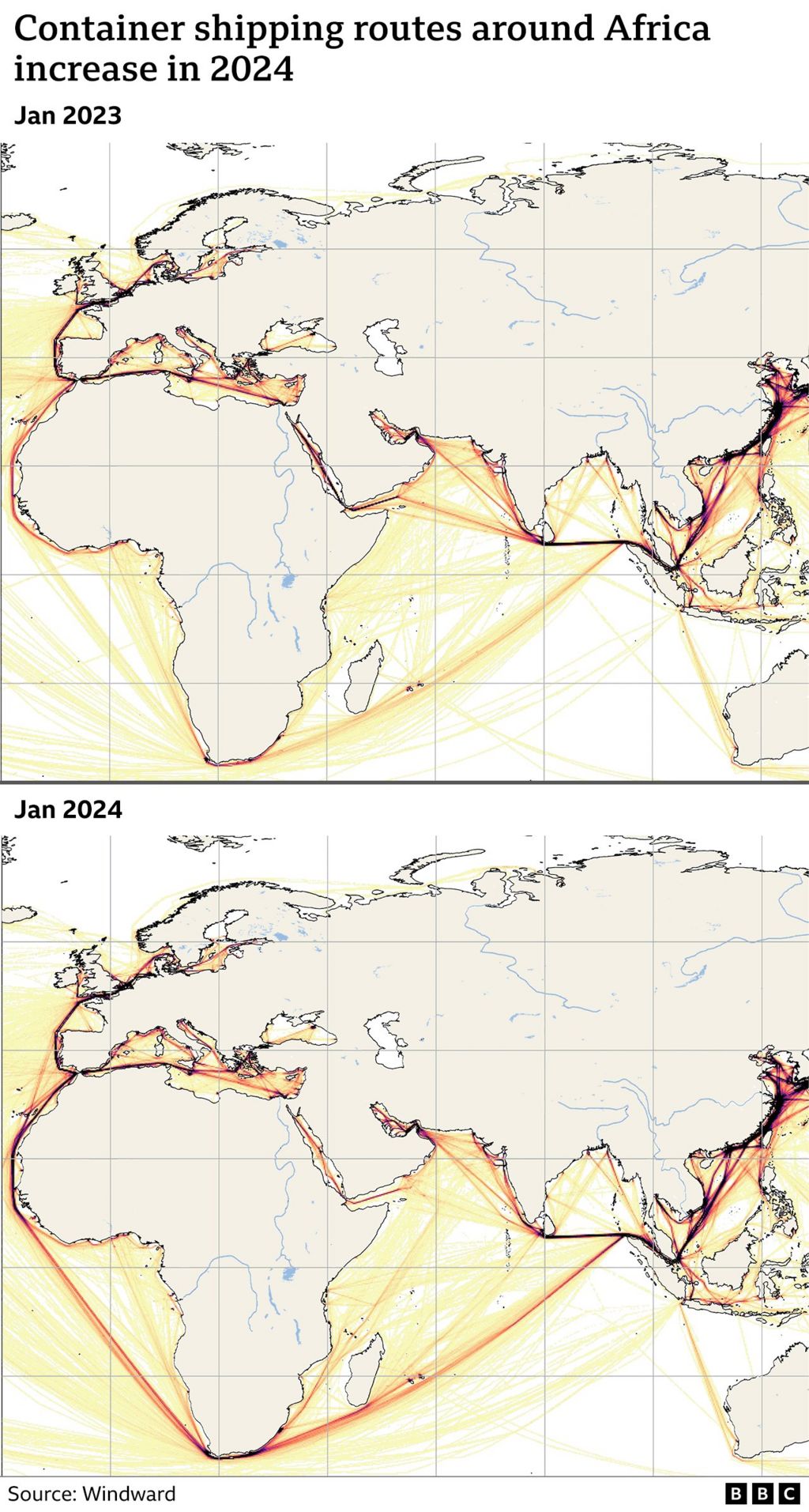

This map, based on data from the maritime AI company Windward, shows significantly higher traffic around Africa in January 2024 compared with the same period last year.

With fewer ships passing through the Suez Canal, the canal’s governing body says its revenues in January have dropped by 44% compared with the same month in 2023.

It’s also anticipating revenues to decline by 40% this year to $6bn on the assumption that the shipping crisis in the region will continue.

Data from Lloyd’s List Intelligence indicates that this is particularly true of certain vessel types such as container ships – where a small number of companies, like Maersk, control large portions of the global tally of ships.

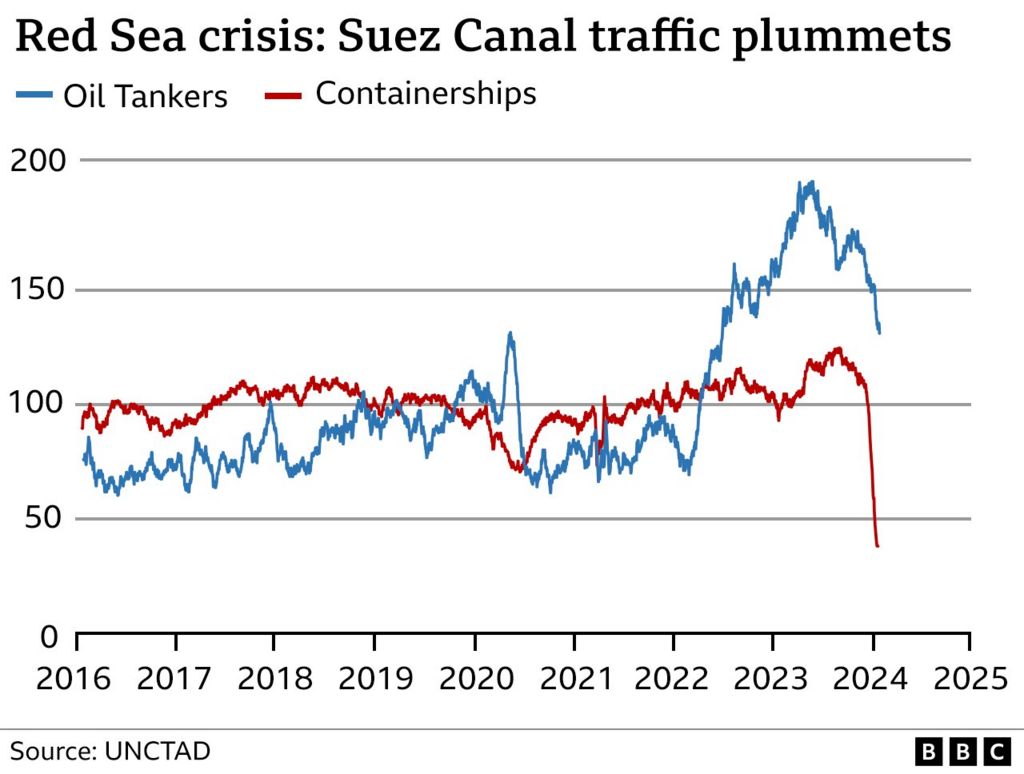

The number of oil tankers using the Suez Canal had almost doubled over the past two years, as sanctions against Russian energy forced European countries to source oil and gas from Asia.

That has fallen since the Houthi attacks started, though not as dramatically as for container shipping.

Mitigating the risks

Ship operators choosing to risk the dangers of the Red Sea route have adopted various measures to reduce the possibility of attack.

Some companies are paying for armed security teams on board their vessels to repel any hijacking attempts.

Others have disabled their on-board AIS tracking – the system all commercial shipping uses to allow their position and declared route to be monitored – making it harder for Houthi forces to locate them.

Some have taken to declaring “no link to Israel” on their location equipment, or have written “armed guards on board” or “all Chinese crew” – underscoring what ship owners believe will deter attackers.

Some Chinese companies have capitalised on assurances of safe passage by the Houthis, and Lloyd’s List Intelligence says that the proportion of Chinese-affiliated shipping has increased since the end of November from 13% to 28% of all vessels passing through the Red Sea.

Comments (0)