The 14th Amendment plan to disqualify Trump, explained

A longshot legal bid in multiple US states to disqualify Donald Trump from the 2024 US presidential ballot has led to him being kicked off the ballot in Colorado and Maine.

The strategy involves trying to block Mr Trump from the primary ballot by invoking a rarely used provision of the US Constitution – Section 3 of the 14th Amendment – that bars those who have “engaged in insurrection or rebellion” against the country from holding federal office.

Initially backed by liberal activists, the theory that Mr Trump was ineligible to run for the presidency again after the 6 January Capitol riot gained more prominence in recent months as some conservatives also embraced it.

The Colorado Supreme Court was the first to offer legal backing to the idea, ruling on 19 December that Mr Trump be removed from the state’s 2024 presidential ballot.

It was the first time that Section 3 of the 14th Amendment was used to disqualify a presidential candidate.

Maine’s top election official – Democratic Secretary of State Shenna Bellows – then ruled on 28 December that Mr Trump could not run for president in the state, also citing the 14th Amendment.

Both rulings are on hold pending appeal, but critics have warned that if the cases move forward they risk robbing voters of the right to deliver their own verdict on whether the former president should return to the White House.

What is the theory?

The 14th Amendment was ratified after the American Civil War, and Section 3 was deployed to bar secessionists from returning to previous government posts once southern states re-joined the Union.

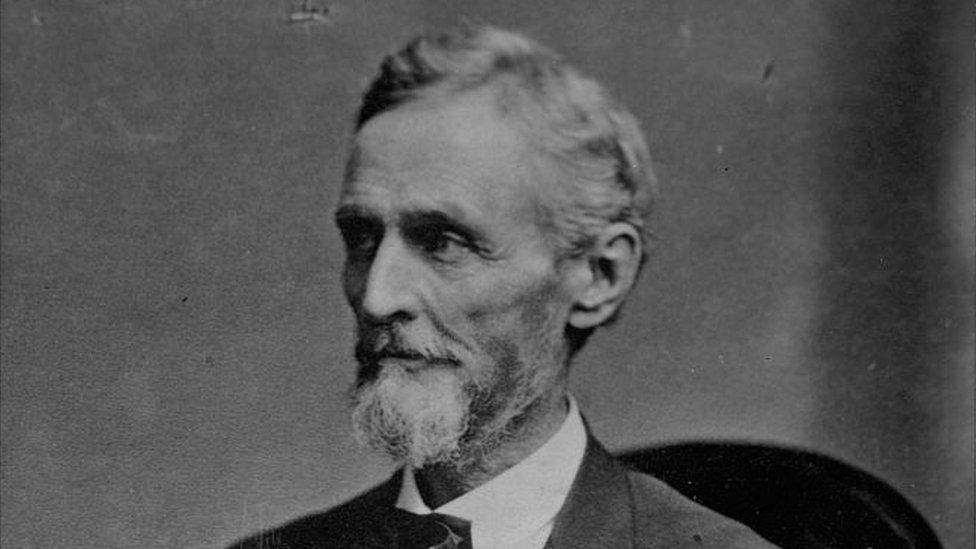

It was used against the likes of Confederate president Jefferson Davis and his vice-president Alexander Stephens, both of whom had served in Congress, but has seldom been invoked since.

It re-emerged as a political flashpoint in the wake of Mr Trump’s effort to overturn his 2020 election defeat, which culminated in the riot at the US Capitol in January 2021.

In the riot’s aftermath, the US House of Representatives impeached the then-president on a charge of “incitement of insurrection”.

Had the US Senate voted to convict him, it would have had the option to take a second, simple-majority vote to bar him from ever serving in office again.

But that never happened: the Senate failed to reach the two-thirds majority required to convict Mr Trump, so there was no second vote.

Does Section 3 apply to Trump?

Free Speech For People, an advocacy group, has been arguing that it does. On behalf of a group of voters, it filed motions in early January in Illinois and Massachusetts to remove Trump from those state’s ballots.

Last year, the group filed challenges against five Trump-backing lawmakers whom it labelled “insurrectionists”.

One – against Georgia congresswoman Marjorie Taylor Greene – was heard in court but ultimately defeated.

The 14th Amendment was not written solely to apply to the Civil War’s immediate aftermath, but also to future insurrections, argues Ron Fein, the organisation’s legal director.

He told the BBC the US Capitol riot succeeded “in delaying the peaceful transfer of power for the first time in our nation’s history, which is further than the Confederates ever got”.

“The particular candidates we challenged in 2022 had participated or assisted in the efforts that led up to the insurrection,” Mr Fein said.

All these cases, he argued, established important legal precedents that can be applied to show “Trump is the chief insurrectionist”.

In New Mexico, a challenge brought by the Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington (Crew) watchdog group saw Couy Griffin, a local county commissioner who participated in the Capitol riot, removed from office under Section 3 – the first such ruling since 1869.

How will it move forward?

The case in Colorado challenging Mr Trump’s eligibility was filed by Crew on behalf of six state residents.

The group is also separately petitioning the top election officials in at least 18 states to remove Mr Trump from the primary ballot.

The legal strategy has picked up steam since August, when Mr Trump was accused of election subversion in two separate criminal cases.

That same month, conservative legal scholars William Baude and Michael Stokes Paulsen wrote in a law review paper that Section 3 is “self-executing, operating as an immediate disqualification from office, without the need for additional action by Congress”.

Mr Trump could therefore be rendered ineligible for election, the pair concluded.

Mr Baude and Mr Paulsen are members of the Federalist Society, a highly influential conservative advocacy group, and their stance has since been backed by other legal experts with conservative credentials.

Even the Supreme Court, with its conservative majority and trio of Trump-appointed judges, may be receptive to their argument, said Jeffrey Sonnenfeld, a dean at the Yale School of Management who supports the Baude-Paulsen perspective.

The top court will hear the Colorado case in February, by which time the Republican primary contest to pick the party’s presidential nominee will have already begun.

What’s the argument against it?

Detractors have questioned both the theory’s viability, and whether it should even be implemented in a highly partisan America.

“To make a tortured legalistic logic to try to stop people from voting for who they want to vote for is a Soviet-style, banana republic argument,” said New Hampshire Republican Party chairman Chris Ager.

“I’m not a Trump supporter. I’m neutral,” he added. “But this whole attempt is bad for the country.”

Even Brad Raffensperger, a Republican and the top election official in Georgia and a previous target of Mr Trump’s ire, rejected the move as “merely the newest way of attempting to short-circuit the ballot box”.

What does Trump say?

Despite his mounting legal troubles, Mr Trump remains the dominant frontrunner for the Republican nomination and is polling neck-and-neck with President Joe Biden ahead of their expected rematch.

The Trump campaign has said that the legal challenge is “stretching the law beyond recognition” and has no basis “except in the minds of those who are pushing it”.

Mr Trump’s attorney in the Colorado case argued that the twin dismissals in Michigan and Minnesota were evidence of “an emerging consensus here across the judiciary”. A third dismissal in Arizona has further aided their case.

“The petitioners are asking this court to do something that’s never been done in the history of the United States,” Scott Gessler said. “The evidence doesn’t come close to allowing the court to do it.”

Comments (0)